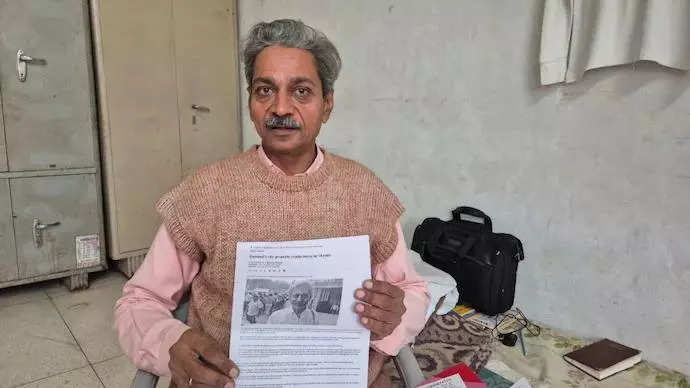

AGRA: When Hemant Jain first set his sights on a 144-square-foot shop in Mumbai’s Nagpada area, he saw more than property; he saw a chance to defy the underworld’s shadow. “I bid for the property after reading in a newspaper that Dawood’s properties weren’t attracting buyers,” he said. That was 23 years ago, and Jain was 34. What followed was a journey of Kafkaesque bureaucracy, ballooning costs, and an enduring clash of wills — all for a piece of real estate tied to one of India’s most notorious underworld figures, Dawood Ibrahim.

Jain, now 57, purchased the property in Sept 2001 during an auction conducted by the income tax department, paying Rs 2 lakh for the shop on Jayraj Bhai Street. But the celebration was short-lived. “After I purchased the property, officials misled me, claiming a ban on transferring Centre-owned properties. Later, I found no such ban existed,” he said.

From that moment, the bureaucratic roadblocks came thick and fast. The I-T department claimed the “original files were missing,” leaving the ownership transfer process in limbo. Despite repeated letters to the Prime Minister’s Office — spanning the tenures of Atal Bihari Vajpayee, Manmohan Singh, and Narendra Modi — progress was elusive.

By 2017, the property file vanished entirely, and Jain was told to pay stamp duty based on the current market value, which had soared to over Rs 23 lakh. Registration fees and penalties compounded his financial woes. “Since the property was bought in the auction, the stamp duty should not have been calculated as per the market value,” he argued. “I kept following up with the registrar’s office for several years but received no response.”

Undeterred, Jain paid Rs 1.5 lakh in stamp duty and penalties, and on Dec 19, 2024, the property was finally registered in his name. “I won’t abandon this fight. Now that the property is in my name, I will also secure possession,” he declared.

But victory remains incomplete. The shop is still occupied by alleged henchmen of Dawood, who have turned the space into a lathe machine workshop. Jain’s frustration is evident, but so is his resolve. “Authorities advised me to forget about the property and live peacefully,” he said. “But we villagers don’t know fear. A man from the village is like a banyan tree — strong against all winds.”

The shop was among many assets seized under the Smugglers and Foreign Exchange Manipulators (Forfeiture of Property) Act (SAFEMA), part of the govt’s crackdown on Dawood’s empire. Jain and his elder brother, Piyush, were the first to purchase such a property—a move that encouraged others to follow suit.

Jain’s defiance didn’t go unnoticed. Political figures like Ramjilal Suman, Samajwadi Party’s national general secretary, and former MLA Azeem Bhai wrote to the state govt, recommending that Jain be honoured for his courage. For Jain, however, the fight transcends the physical boundaries of the shop. “The primary reason I bought this property was to challenge Dawood Ibrahim’s dominance,” he said.

Jain, now 57, purchased the property in Sept 2001 during an auction conducted by the income tax department, paying Rs 2 lakh for the shop on Jayraj Bhai Street. But the celebration was short-lived. “After I purchased the property, officials misled me, claiming a ban on transferring Centre-owned properties. Later, I found no such ban existed,” he said.

From that moment, the bureaucratic roadblocks came thick and fast. The I-T department claimed the “original files were missing,” leaving the ownership transfer process in limbo. Despite repeated letters to the Prime Minister’s Office — spanning the tenures of Atal Bihari Vajpayee, Manmohan Singh, and Narendra Modi — progress was elusive.

By 2017, the property file vanished entirely, and Jain was told to pay stamp duty based on the current market value, which had soared to over Rs 23 lakh. Registration fees and penalties compounded his financial woes. “Since the property was bought in the auction, the stamp duty should not have been calculated as per the market value,” he argued. “I kept following up with the registrar’s office for several years but received no response.”

Undeterred, Jain paid Rs 1.5 lakh in stamp duty and penalties, and on Dec 19, 2024, the property was finally registered in his name. “I won’t abandon this fight. Now that the property is in my name, I will also secure possession,” he declared.

But victory remains incomplete. The shop is still occupied by alleged henchmen of Dawood, who have turned the space into a lathe machine workshop. Jain’s frustration is evident, but so is his resolve. “Authorities advised me to forget about the property and live peacefully,” he said. “But we villagers don’t know fear. A man from the village is like a banyan tree — strong against all winds.”

The shop was among many assets seized under the Smugglers and Foreign Exchange Manipulators (Forfeiture of Property) Act (SAFEMA), part of the govt’s crackdown on Dawood’s empire. Jain and his elder brother, Piyush, were the first to purchase such a property—a move that encouraged others to follow suit.

Jain’s defiance didn’t go unnoticed. Political figures like Ramjilal Suman, Samajwadi Party’s national general secretary, and former MLA Azeem Bhai wrote to the state govt, recommending that Jain be honoured for his courage. For Jain, however, the fight transcends the physical boundaries of the shop. “The primary reason I bought this property was to challenge Dawood Ibrahim’s dominance,” he said.