NEW DELHI: They once posed a challenge to the dominance of Congress and BJP in the electoral politics of the capital. However, several prominent national and state parties, which even won a few seats in different elections, slowly faded away in ignominy and have no relevance left in the city politics now.

The unrecognised registered parties, which have also been a regular feature in all Lok Sabha, state assembly and municipal polls over the years, too, have failed to rise beyond being just a statistic in the reports prepared by Election Commission after the conclusion of the exercise.

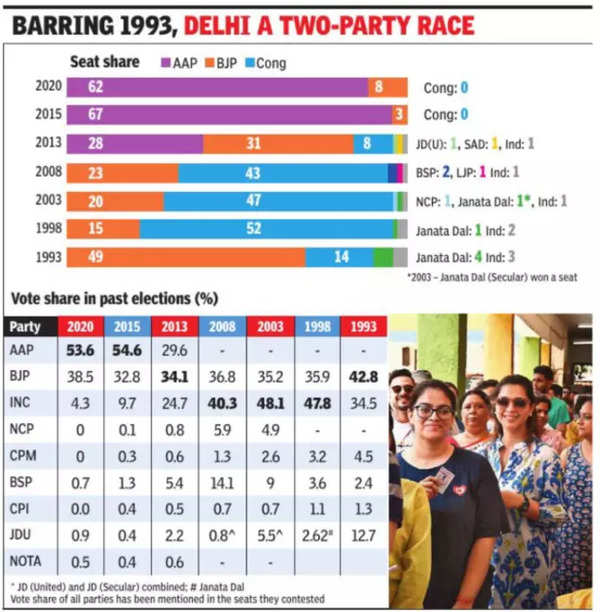

Delhi’s electoral politics, which has always been known for the dominance of two political parties, continues to remain the same – only a player has changed in the equation in the last decade. While it was Congress and BJP earlier, the emergence of AAP in 2013 changed the dynamics. The rise of the Arvind Kejriwal-led party not only led to the decimation of Congress, with the core voter base of the grand old party shifting its loyalties to the then political greenhorn, but the small vote banks of other national and state parties also gravitated towards AAP.

As a result, a majority of votes polled in the last few years either went to BJP or AAP, depending on whether it was the parliamentary election or the assembly polls, while only a fraction came to the kitty of the remaining players in the fray, including independents.

The election of 1993, first after the reconstitution of Delhi legislative assembly, saw six national, three state, and 41 registered unrecognised parties throwing their hats in the ring. While three parties – BJP, Congress and Janata Dal – nominated candidates on all 70 seats, most chose to contest in a select few constituencies. A total of 1,316 candidates, including 766 independents, were in the fray. While six national parties together polled 90.6% of votes, the three state parties got a meagre 2%, registered unrecognised players barely 1.3% of votes, while all independent candidates together got a vote share of 5.9%.

Of the six national parties, BJP and Congress got 42.8% and 34.5%, while Janata Dal got 12.7%, and the remaining three got a meagre 0.8% of votes. While Janata Dal managed to win four seats, three independent candidates were also elected.

The city, which has nearly 17% of Dalit voters, with 12 of 70 seats reserved for them, and having the power to tilt the election outcome in another 5-7 constituencies, saw the rise of Bahujan Samaj Party in the subsequent polls. From 1.9% in 1993, the party’s vote share increased to 3.6% in 1998, and 9% in 2003. The year 2008 saw BSP putting up its best-ever performance by winning a healthy 14.1% of votes and two seats in the assembly. The rise of AAP, which grew as a messiah of the poor in 2013, saw a sudden drop in the popularity and support of all smaller parties. In 2015, AAP, BJP and Congress together polled 97.1% of votes while the remaining four national, nine state, 53 registered unrecognised parties and 195 independent candidates together got 2.9% of votes. The situation was similar in 2020, when AAP, BJP and Congress secured 96.6% and the rest of the players got the remaining 3.4%.

Ravi Ranjan, a professor of Political Science in Delhi University’s Zakir Husain Delhi College, said the prime objective behind forming a political party was to be active in electoral politics and show that they were serious players in this business. “Every political party, whether it is a national or a state player or an unrecognised group registered with Election Commission, has to show the world it is actively engaged in politics and that’s why they participate in the electoral process, despite knowing the possible outcome fully well,” Ranjan said.

“Also, all political players aspire to be known as state- or national-level parties, for which they have to contest elections and get a certain percentage of votes as fixed by EC. It is a statutory requirement. If you don’t fight an election, where and why will these parties get the funding from their sponsors?” he added.

While prominent national and state parties genuinely try to spread their wings in other states and contest to make a difference, experts believe on many occasions the candidates of registered unrecognised parties and independents are used by bigger political players to “cut” into the votes of the rivals.

“Often, the candidates of a particular religion or caste or affiliation are put up to confuse voters. Candidates with similar-sounding names of a prominent one in that particular constituency are also made to contest. If there are a number of candidates in a particular constituency with different symbols, the voter may get confused and votes might get divided,” said a veteran political functionary who worked as a back-end resource in a large number of elections.