Among all other things, India paid a heavy price for its conservative approach of lengthening the batting line-up by including allrounders

SYDNEY: There is no way to sugarcoat this. The long Australian summer has broken Indian cricket’s back. The team now needs to spend time in the infirmary before the next big challenge, the five Test series in England in the middle of the year.

Go Beyond The Boundary with our YouTube channel. SUBSCRIBE NOW!

What would have been a celebration of a wonderful series which drew record crowds now needs to be a dissection of India’s failings. For Rohit Sharma‘s men, this has been a series of missteps, one bigger than the other. Any introspection must feature some key considerations. Most of them revolve around team composition and dressing-room atmosphere.

One is whether the team paid the price for its conservative approach of lengthening the batting order by including allrounders. The second is whether that decision was prompted by the desire to safeguard the spots of some spent forces.

The third is owning responsibility for the decision to bowl Jasprit Bumrah to the ground by consistently denying him the support of a frontline fourth pacer in seaming conditions.

Over-reliance on Bumrah led to his breakdown in Sydney, preventing him from playing a part as India failed to draw the series. Was it merely wishful thinking that Bumrah would pull through, or was a more scientific assessment made of his increasing workload through the series?

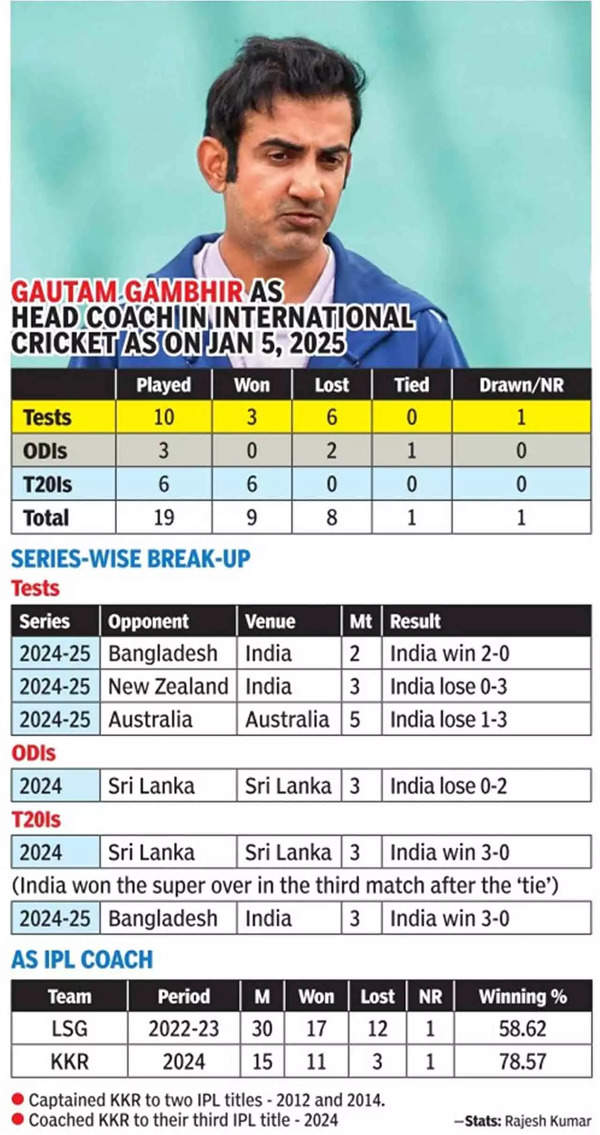

That brings us to the role of the backroom staff, and whether new head coach Gautam Gambhir and his support personnel did enough to quell the chaos as panic and confusion set in the ranks following the MCG defeat.

That last bit is important because Australia skipper Pat Cummins, whose team resembled India in many ways at the start of the series – a bevy of senior players, two main batters facing prolonged run drought, talk of transitioning to the younger lot – said staying calm after defeat in the first Test in Perth had played a big role in their success.

“When you start a series behind, a lot of things get questioned, fairly or unfairly. It shows the strength of the group to stay strong, know that we weren’t at our best but can get better, know we won’t get caught up in the external noise and clutter, and just focus on what makes us good players and a good team,” Cummins said here after Australia reclaimed the Border-Gavaskar Trophy after a decade. “More than what you change, it’s about what you don’t change.”

In contrast, as rumours swirled around captain Rohit dropped for the fifth Test, the team management added to the intrigue by refusing to make things official. What happened off the field seemed to affect India on it.

The team was flying high after Perth on the form of Bumrah, a generational talent with the uncanny ability to peak at the right moments. It was the return of their regular captain from paternal leave that seemed to upset the balance of the XI.

Some baffling decisions were made, all to goad Rohit into regaining some sort of form. KL Rahul was retained as opener, shuffled to No. 3 and shifted back again once Rohit realized in Sydney that runs had deserted him.

Shubman Gill’s overseas record is poor, but he had got starts in Adelaide before being unceremoniously dropped in Melbourne as Rohit decided to reclaim his opening slot.

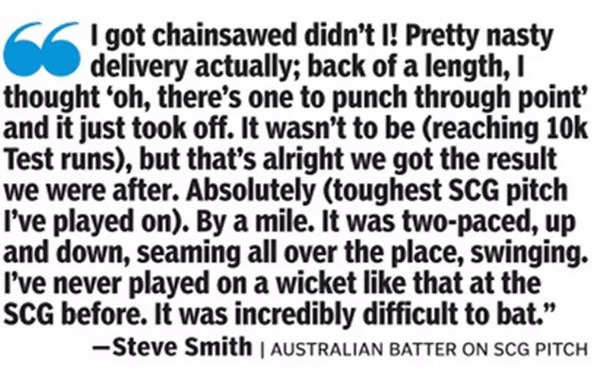

There were other strange decisions, like playing two spinners on the Sydney green top, the most difficult batting surface in the series. Why wasn’t a fourth frontline seamer or even a regular batter picked in place of Washington Sundar?

With Bumrah unavailable, the end result was that Prasidh Krishna and Mohammed Siraj bowled 24 of the 27 overs as Australia cantered to the 162-run target.

Nitish Reddy as fourth seamer was another contentious choice. His gentle medium-pace let off the pressure on the Aussie batters and ensured the main seamers didn’t get enough breaks. The other bowling options were spinners, in Ashwin, Jadeja and Sundar, and were of little use on these pacy surfaces.

At times, the team composition even seemed T20 driven, no surprise given that the coach and captain’s credentials stem from T20 success.

Asked after the Melbourne defeat if he was happy to pack his side with batting allrounders instead of another frontline seamer, Rohit said, “Akash (Deep) and Siraj are the frontline seamers (to support Bumrah). It’s just that they’ve been very unfortunate not to be seen on the wickets column. These are the three frontline seamers and whoever plays needs to get the job done for the team.”

Reddy’s momentous century at No. 8 at the MCG was an immediate pointer to the poor form of stalwarts Virat Kohli and Rohit up the order. Both came to Australia hoping to tide over what seemed like terminal decline. Both failed in spectacular fashion.

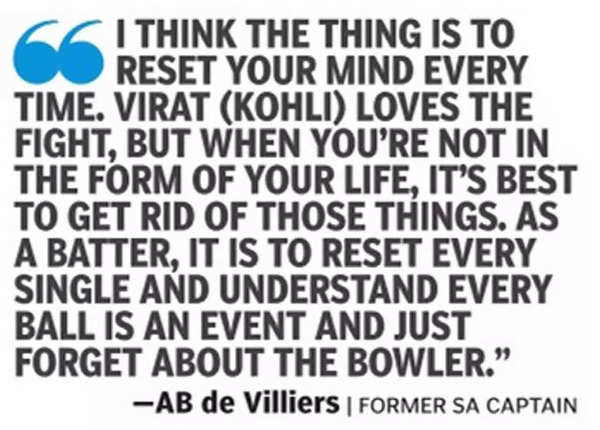

Kohli’s weaknesses outside off-stump and technical failings eventually made him a walking wicket after a strong start in Perth, where he got to face the old Kookaburra ball and scored a century.

Kohli now averages 32.29 from his last 40 Tests, 22.47 in 2024, and 23.75 from these five Tests Down Under. All eight of his dismissals were identical, caught behind on the off side, trying to drive deliveries on the fifth or sixth stump line. Scott Boland got him four times, making for one those nice subplots which lit up the series.

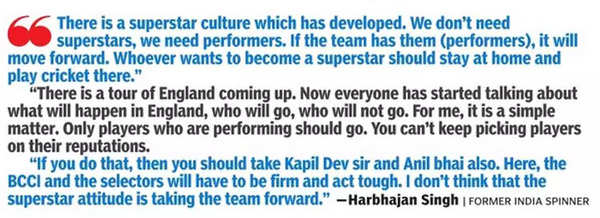

Surely there is something more going on with Kohli than a temporary dip in form? It could be slowing reflexes or ageing eyesight. It doesn’t seem like it is a loss of focus, given the extraordinary effort Kohli has put in the nets across these five Tests here. What should Team India do with its biggest brand and batting talisman? Shouldn’t his Test place be up for debate? Are the stars taking their places for granted?

As for Rohit, he is a lesser Test batsman than Kohli but an important one, nevertheless. His entire season has been a horror run and that affected his captaincy too. He dropped himself in the fifth Test to save face and his return cannot be dependent on white-ball form.

“Not a lot of people are playing for the first time in Australia, probably two in the top eight,” Gambhir said. “(Other than) Nitish (Reddy) and Yashasvi (Jaiswal), all the others have the experience of Australia. I’m not going to say it is only because some of the young guys (that India lost). There are a lot of experienced players as well,” Gambhir said.

Even if the team management and selectors are in a hurry to see the backs of Kohli and Rohit, where are the replacements? Can Reddy be a regular Test No. 4? Can KL Rahul, and if so, who opens with Jaiswal?

Where are the new breed of Test pacers to support Bumrah? Can Bumrah, given his injury breakdowns and workload-management necessities, take on regular captaincy duties?

This was the shortest-ever five-Test series played in a century, lasting 7,664 balls. How much did India’s batting failures contribute to that? It’s all right saying players must return to domestic cricket, like Gambhir did after the Sydney defeat, but the watered-down standards of tournaments like the Ranji Trophy are unlikely to be of much help.

“Ultimately, it is neither my team nor your team, it’s the country’s team. There are very honest players in our dressing room who know how hungry they are, and how the Indian team (can) go ahead with their contributions. As far as my question is concerned, my biggest responsibility is that I have to be fair to everyone, not only one or two individuals,” Gambhir said.

Known as a confrontational character in his playing days, Gambhir knows his own job is under the scanner, given India’s poor record since he took over.

Questions are being raised why the assistant coaches need to be changed with every new head coach.

Gambhir’s role may have started with talk of transition, but it will eventually need to move on to identifying and nurturing top talent. England will be a stern test.