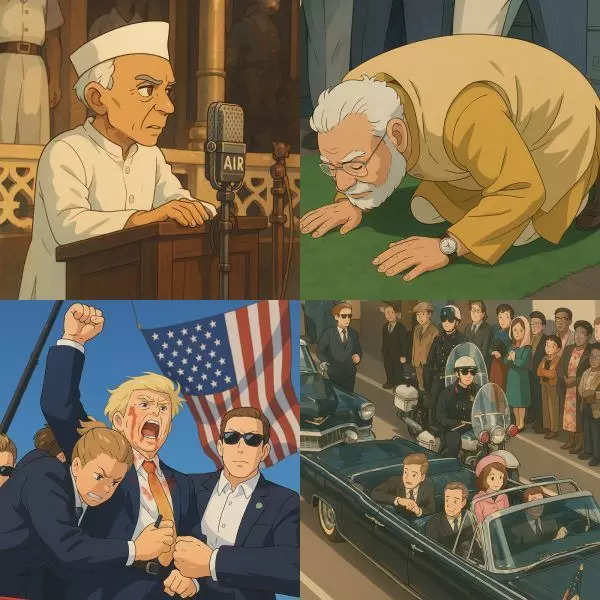

What does Donald Trump being shot at have in common with Shah Rukh Khan spreading his arms wide in a mustard field? What unites a lone protester at Tiananmen Square and a wedding in Kolkata? They have all been turned into Ghibli portraits—at least for a moment.

Yes, that Ghibli. The hand-drawn dreamscape of Hayao Miyazaki. The soft-lit realm of spirits, forests, flying castles, and girls with wind-tousled hair—now transposed onto our memories and icons, courtesy of artificial intelligence. A new filter that harks back to the cartoons we grew up with, as social media user @Gabbbar pointed out. But is it something more?

In Being and Nothingness, Jean-Paul Sartre argued that human existence is not defined by what we are, but by what we project ourselves toward. We are not fixed beings—we are always becoming, shaping our identities through imagined futures, chosen selves, and ideal versions of who we might be. In this sense, every Ghibli-style portrait is more than stylised nostalgia; it’s existential projection—a quiet act of longing. AI does not merely render an image; it renders a desire—like what we might see in the Mirror of Erised from the Harry Potter universe, which shows our deepest wants.

Protest, romance, childhood, catastrophe—all reimagined in the palette of Spirited Away, My Neighbour Totoro, and Howl’s Moving Castle. Not painted by human hands, but summoned by code—each frame a whispered wish for the world to have been gentler, softer, more beautiful than it was.

With OpenAI’s latest ChatGPT update, the Ghiblification of memory began—and ended, just as abruptly.

The AI Behind the Aesthetic

On March 26, 2025, OpenAI rolled out one of the most emotionally resonant updates in recent memory. ChatGPT, powered by GPT-4o, briefly allowed paid users to generate and edit images natively. Upload a selfie, a wedding photo, a political moment—and the model, built on DALL·E 3, reimagines it in a painterly, melancholic style unmistakably Ghibli-esque.

Shah Rukh Khan’s outstretched arms become a frame from a Japanese love story. A scene of violence becomes strangely tender. Even war zones take on the quiet sorrow of a Miyazaki landscape.

OpenAI’s model may not say “Ghibli” aloud—but it doesn’t have to.

From Spectacle to Storybook

There’s something extraordinary about the speed with which this trend spread. It wasn’t just selfies being transformed—it was history. Moments once captured through the harsh clarity of journalism were suddenly stylised into soft, glowing pastels where even suffering seemed to pause and exhale.

Studio Ghibli’s aesthetic has never been about fantasy in the Western sense. It’s about intimacy. Founded in 1985 by Hayao Miyazaki, Isao Takahata, and Toshio Suzuki, the studio’s films brought a radical softness to the screen. They showed us that wonder exists in quietness, that beauty hides in overlooked places—a bowl of ramen, a walk to school, a forest spirit watching silently.

That aesthetic has returned—this time through artificial intelligence—as a kind of cultural balm. And people responded in kind.

The Mirror We Love

Part of the enchantment lies in what these Ghibli-style portraits gently erase. Hair appears fuller, skin smoother, eyes brighter. The small imperfections that define us are softened or omitted entirely. Our faces are lit in warm hues and golden light. We don’t just look better—we look loved.

In a society obsessed with harsh clarity, these portraits offer a version of ourselves that feels timeless and quietly transcendent. Not necessarily perfect, but poetic.

It’s like seeing your reflection in the Mirror of Erised—not as you are, but as you hope to be.

The Illusion of Becoming

But beauty, when too easily granted, can also lull us into forgetting the responsibility that comes with being real.

Jean-Paul Sartre taught that we are not what happens to us—we are what we do with what happens to us. We are condemned to be free. And there is no freedom in looking at idealised versions of ourselves, over and over again.

To project ourselves into better light is not inherently false—but it becomes dangerous when we begin to believe in those images more than in the difficult, often unglamorous work of becoming.

That’s where the Ghibli-style images, for all their charm and warmth, quietly betray us.

They give us the illusion of transformation without requiring action. They offer beauty without process, intimacy without vulnerability, nostalgia without memory. They turn projection—a necessary part of growth—into a screen we hide behind.

Sartre warned that when we use projection to escape rather than engage, we fall into bad faith—a denial of our freedom, a refusal to take ownership of the self we are constantly creating. In that sense, these AI-crafted dreams, however lovely, risk becoming a form of self-deception.

The Ghibli-style image is both a gift and a mirror. It reflects not what we are—but what we wish the world would make of us. Whether that is art or artifice, memory or fantasy depends on whether we still choose to live in the reality that lies just beyond the frame.

Because in the end, the most beautiful image is not the one that flatters us—but the one we are still free to change.

The Ethical Question

Then there’s the ethical issue. Critics have accused the trend of aestheticising pain, trivialising culture, and flattening an artistic tradition that was never meant to be a filter. In fact, it’s arguably an intellectual property violation—borrowing years of painstaking craftsmanship without permission or compensation.

As illustrator Robbie Shilstone wrote on X: “Miyazaki spent his entire life building one of the most expansive and imaginative bodies of work, all so you could rip it off and use it as a filter for your vacation photos. Not into this one bit. Protect artists.”

He added: “I can’t think of a worse artist to do it to. He is notorious for his attention to detail, his painstaking revisions, his uncompromising dedication to his craft. Now it’s just viewed as content… it’s a real shame.”

Ghibli is not just a style. It is the result of decades of devotion, slowness, and care. To distil it into a look, reproduced in seconds, feels to many like a betrayal of what the studio stands for.

Even Hayao Miyazaki himself was vocally disgusted by the concept of AI-generated animation. When shown a prototype of AI-generated movement in 2023, he called it “an insult to life itself.”

Legally, there’s little recourse. Ghibli’s characters and trademarks are protected, but its tone, colour palette, and emotional cadence are not. A machine can copy the look, even if it can’t understand the soul behind it. After all, ChatGPT itself was ostensibly trained on the work of countless creators. But for those who believe art is sacred, that distinction still matters.

Reality Reasserts Itself

As quickly as the Ghibli wave arrived, it began to recede. The latest message now reads: “I couldn’t generate the Ghibli-style image from your latest upload due to content policy restrictions around generating images based on real individuals.” Of course, this could simply be a feature of an overload and there are other options that can be used to create these images.

The restriction seems to be OpenAI’s response to the sheer volume of uploads involving real people—celebrities, political figures, loved ones. As AI-generated likenesses of public and private lives flooded social media, OpenAI likely reinforced its content policy prohibiting visual recreations of identifiable individuals without consent.

Though stylised and abstract, these portraits tread dangerously close to real likeness. The restriction isn’t just a technical adjustment—it’s a reminder: even dreams drawn in pastel must reckon with the rules of reality. Freedom, after all, is what we do with what’s been done to us. For a brief moment, that meant reimagining ourselves as Ghibli. But like all things, that too must pass.