In 1947, when the British transferred power to India and Pakistan, many businesses also changed hands. One of them was Murree Brewery, among the oldest distilleries in Asia, which was then largely owned by a British family. The Bhandaras of Lahore became its new owners. They were a Parsi family that had thrived in the liquor business.

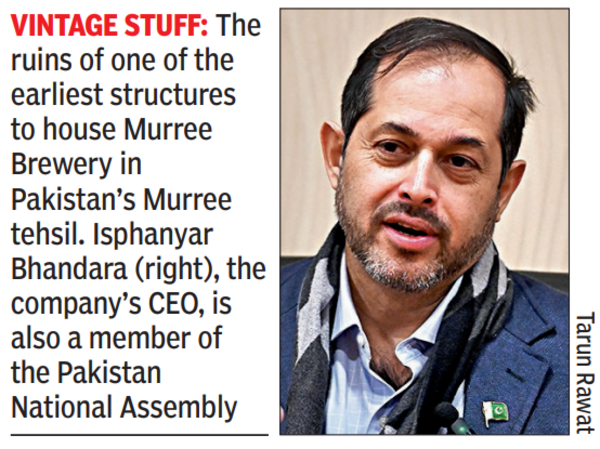

Isphanyar Bhandara now runs Pakistan’s top brewery.He recently made a brief halt in New Delhi on his way to Nepal. “It’s my tenth visit to India,” the businessman-politician said cheerfully, a Pakistan flag lapel pin on his coat the only green in his otherwise blue attire.

Liquor business is heavily regulated in the Islamic Republic of Pakistan. About 96% of the country’s population is Muslim. The brewery, accordingly, points out on its website, “Under the country’s laws Pakistan Muslims are prohibited from consuming alcoholic drinks. Non-Muslims and foreigners require a consumption permit.”

Nonetheless, the business has been rewarding for the Bhandaras. “The forbidden fruit is always sweet,” said Isphanyar. “We make beers from Australian barley. Our vodkas and single malts are also doing very well. It’s all about quality. We also make and export fruit juice and are heavily into (bottled) water,” he added.

Success though hasn’t been limited to the arena of trade. Isphanyar is also a member of the Pakistan National Assembly. His father was a central minister under Zia-ul-Haq in the 1980s and an MP during the Pervez Musharraf regime.

But, as a community, the Parsis have wilted. In 1947, Isphanyar says, about 20,000-25,000 of them lived in Pakistan. Like in India, they played a major role in nation-building, especially in cities like Karachi. They were among the top businessmen and jurists and were engaged in philanthropic work. In the 19th century, Parsis were also among the early cricketers of Karachi. According to an article in scoreline.org, a team of Parsi cricketers toured England in 1886. In 1952, when Pakistan’s cricket team toured India, southpaw batter Rusi Dinshaw was part of the squad, although he didn’t get to play a Test.

“Today, we are less than 1,000,” says Isphanyar. “Most of the Parsi population is in its 80s or 90s, a bit like the Japanese. There are very few young Parsis in Pakistan today,” he said.

Many left due to economic reasons, others due to law and order issues. One such migrant was the renowned writer Bapsi Sidhwa, whose novel, Ice Candy Man, was made into a feature film called ‘Earth’ by director Deepa Mehta. Sidhwa passed away in Houston on Dec 25 last year; she was Isphanyar’s aunt.

The 54-year-old businessman gets raw material and machinery from India. “A lot of companies in Pakistan do. The problem is, it is via Dubai,” he said. But there are other reasons why he wants more trade between the two neighbours.

“We can disagree on Kashmir, put it on the back burner. We don’t have to concede our position and India doesn’t have to concede theirs. But we should keep the baggage of history aside and look at the common good of the common people. We should open the Wagah border,” he said.

More business will benefit the underprivileged, he believes. “We need it for the common man – dal, roti, cheeni, stuff like that. It will lower the inflation in Pakistan. I’ve made my presentations to our Prime Minister Shehbaz Sharif saab. I’m keeping my fingers crossed,” he said.

Not many know that the brewery – it gets its name from the scenic resort town – was set up in 1860, just three years after the 1857 revolt, to mainly service British troops. Edward Dyer, father of Reginald Dyer, the perpetrator of the 1919 Jallianwala Bagh massacre, was its first manager. By 1890, water shortage and other logistical issues had forced the distillery to shift to the Rawalpindi area, where it continues to be headquartered.

There was a time when Murree Beer was sold in India. “In fact, Pakistan railways had put up tracks inside the brewery that used to carry beer to places like Kabul, Amritsar and, of course, to Karachi port,” he said. But the state of politics and, consequently, policies, changed in Pakistan in the late 1970s when, exceptions aside, alcohol was banned. But as reputed Dawn columnist Nadeem Paracha wrote in 2013, “Despite the violence and the eventual prohibition on the (open) sale of alcohol and bars in Pakistan in April 1977, Pakistanis never did stop drinking.”

About two decades back, a possible joint venture project proved abortive. “In 2006, when Vijay Mallya (former chairman of United Spirits) visited Pakistan to watch a cricket match, the prospect of doing something together was broached with my father. But politics did not allow them to come together,” he said.

Political relations between the two countries have further dipped now. But Isphanyar is an optimist. He wants the situation to improve. And more Indo-Pak trade, he insists, is the way to begin.