Numerous German streets are named after him, as are hundreds of schools, universities and hospitals. Albert Schweitzer — scientist, doctor, philosopher, theologian, author, musician and Nobel Peace Prize winner — was long revered for his humanitarian work in Africa.

The clinic he set up in Lambarene in present-day Gabon in West Africa earned him the moniker, “jungle doctor.”

But Schweitzer was also a product of his time. Born in 1875 in Alsace, then part of the German Empire, and today eastern France, he was influenced by the ongoing and brutal colonialization of large parts of Africa by European countries.

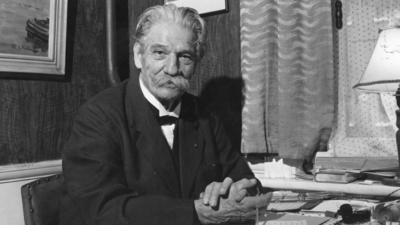

Schweitzer, marked by his flowing mustache and thick head of white hair, was a paternalist who saw himself as being on a kind of “civilizing mission” in Africa. He felt called upon to make the population — which he described as “children without culture” — not only healthy but also “civilized.”

Not a friend of the Nazis — but oddly silent about the Holocaust

The doctor’s fame at home earned him the attention of the National Socialists — despite his early criticism of Hitler.

Later, an invitation sent to Gabon by Joseph Goebbels is said to have been politely declined by Schweitzer.

Having been in Africa almost continuously since 1924, Schweitzer maintained a distance from the horrors of the Holocaust and never condemned the Nazi atrocities, a stance that many researchers have criticized, according to journalist and author Caroline Fetscher.

Fetscher, who has written about Schweitzer’s ambiguous place in German history, believes that the jungle doctor “was well aware of the persecution of the Jews,” despite his isolation.

“However, he neither protested nor raised his voice in any way even after 1945, even if his contemporaries expected and demanded this of him,” Fetscher told DW.

According to Fetscher’s research, most of the doctors working in his hospital in Lambarene at the time of Nazi rule were Jewish. Most had been forced to leave Europe because of the Holocaust.

She explains that a doctor being considered as the future head of the hospital as the successor of the ageing Schweitzer had an Auschwitz number tattooed on his arm.

“Schweitzer knew his story and knew about the atrocities,” said Fetscher.

In addition, Schweitzer’s wife Helene was of Jewish descent and had only narrowly escaped the concentration camps.

Nonetheless, his silence represents “a huge gap in his life,” something numerous biographers have noted, said Fletscher.

Still remembered for saving lives and peace activism

As Schweitzer and his team successfully fought disease and infant mortality in Gabon, this work could conveniently overshadow the crimes of the World War II, according to Caroline Fetscher.

It is therefore no great surprise that many children and young people in postwar Germany regarded Schweitzer as an idol.

Whole school classes wrote him letters, his likeness appeared on stamps, newspaper articles and books also built up his reputation as a heroic, healing philanthropist.

Schweitzer was keen to make amends for what other Europeans had done in the colonies.

“Ultimately, everything good we do for the peoples of the colonies is not charity, but atonement for all the suffering we whites have brought upon them from the day our ships found their way to their shores,” he once said.

Yet Schweitzer did not encourage the emancipatory aspirations of colonized or exploited populations who wanted to build a functioning society or economy without the help of white people.

The polymath used to say to his fellow Africans: “I am your brother. But I am your big brother.”

Despite this paternalistic legacy, Albert Schweitzer is being celebrated as a humanitarian and later a peace activist on the 150th anniversary of his birth.

The world knows him not only as a “jungle doctor,” humanist and animal lover, but also as a tireless fighter against nuclear armament during the Cold War.

He was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1952 for this commitment under the banner of his philosophy, “Reverence for Life.”

As Schweitzer once said: “By having a reverence for life, we enter into a spiritual relation with the world. By practicing reverence for life we become good, deep, and alive.”

Or put another way: “Do something wonderful, people may imitate it.”